Reposted from TheCapeCodFishermen, April 28th 2021

Reposted from TheCapeCodFishermen, April 28th 2021

By David N. Wiley

Bluefin tuna and striped bass crash through the waves. Seabirds wheel overhead and plunge into the water. Gape-mouthed whales rise from below. Schools of cod and dogfish hide below the surface.

While the convergence of such diverse sea life might seem accidental, those in the know thank a small, slender fish called a sand eel for the bonanza.

Also known as sand lance, these three-to-six inch forage fish are a main food source for many of the top predators in the Gulf of Maine and on Georges Bank, including some of the most commercially important species.

As their name implies, sand lance are tied to sand habitat, but not just any sand will do. To avoid predators, sand lance spend most of the night and parts of the day buried. When disturbed, they rocket out of the bottom, then dive head first and at full speed back into the sand.

As a result, their sand of choice has to be coarse enough to hold oxygen for the fish to “breathe” while buried, but soft enough to allow high-speed body penetration. One of the reasons Cape Cod is their Mecca is a band of perfect sand stretching from Stellwagen Bank along the backside of Cape Cod, past Chatham and up through Georges Bank. Whether you are a fisherman, whale watcher or seabird enthusiast, it’s this band of sand, and the sand lance that inhabit it, that makes the Cape special.

Sand and sand lance are the backbone of Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, responsible for it being one of the top places in the United States for viewing marine life, and a centuries old, highly productive fishing ground. Yet while fishermen appreciate the importance of sand lance, little is known about their biology and most of the world does not know they exist.

To remedy the situation, a team of researchers led by scientists from Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary with partners from Boston University, Center for Coastal Studies, University of Connecticut, U.S. Geological Survey and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution have been studying the forage fish to determine its importance and unlock some of its secrets.

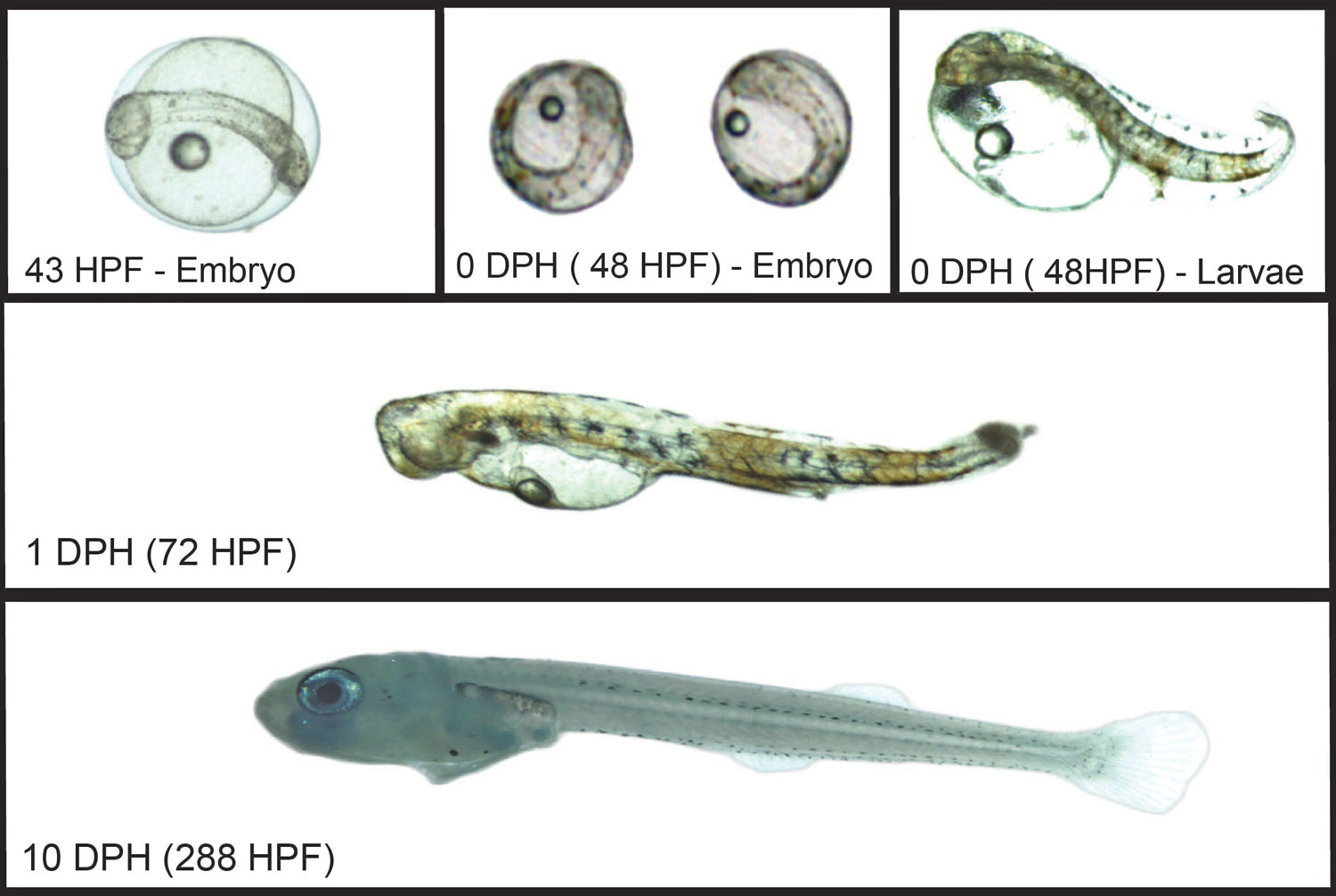

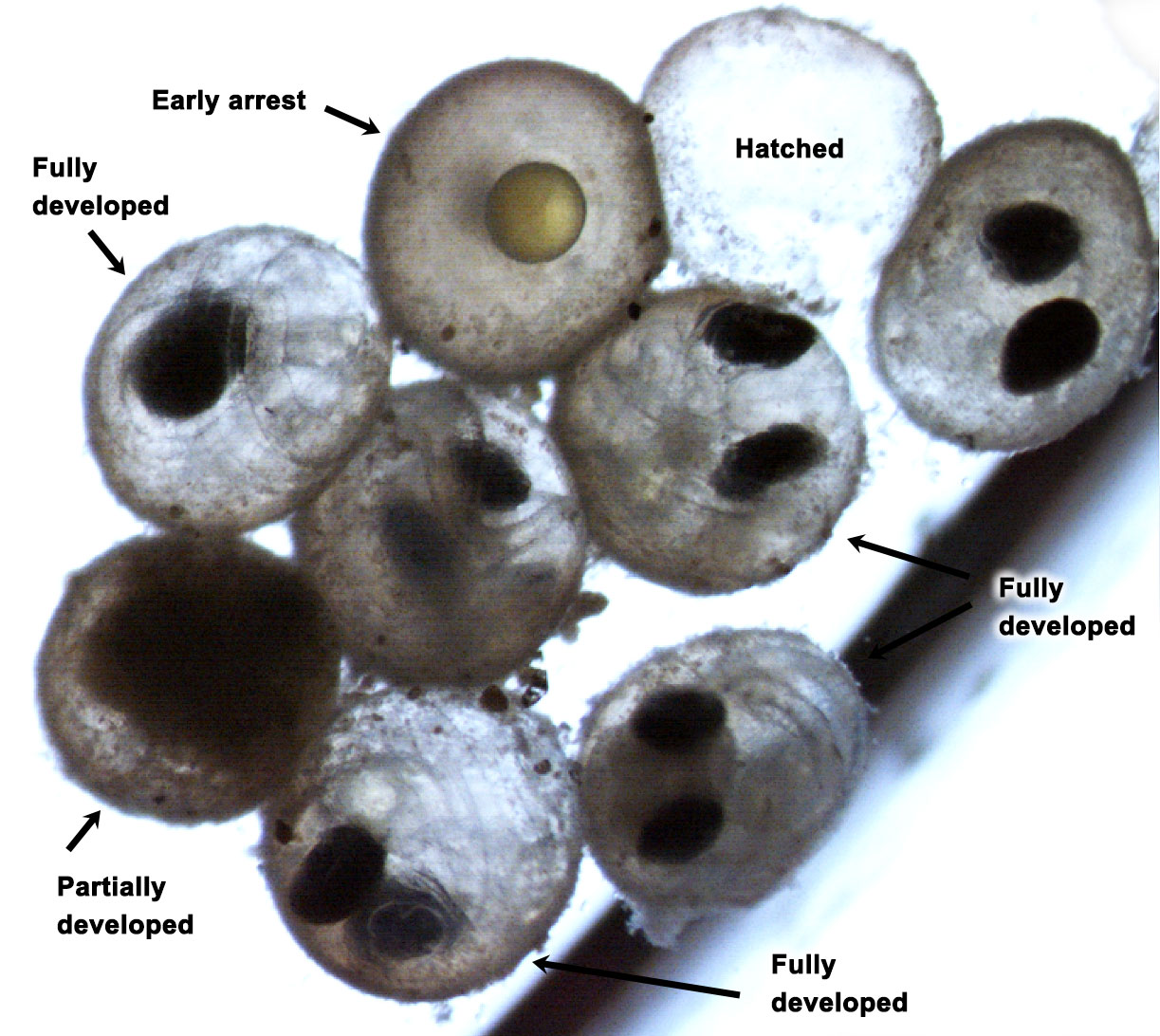

One of the project’s first goals was to identify the sand lance spawning season. Using a specially designed and permitted small-mesh trawl, fished from Steve Welch’s F/V Mystic or NOAA’s R/V Auk, the team captured and examined sand lance. Thought to spawn from late fall through winter, several years of work demonstrated that sand lance on Stellwagen Bank spawn in a very narrow window at the end of November. Eggs are deposited on the seafloor and hatch after approximately six weeks.

Then things get interesting. Once hatched, sand lance are tiny, free-floating larvae for two to three months. Given this long free-floating period and the currents flowing over Stellwagen Bank, many sand lance born on the bank cannot stay there. So where do they come from and where do their offspring go?

To answer this question, the team used hydrographic modeling to backtrack to where free floating particles (like larval sand lance) would have originated prior to their sand settlement in March or April, and where drifting particles would end up two or three months after hatching.

It appears that larval sand lance settling on Stellwagen originate off the coast of Maine; years of highest sand lance abundance correspond to conditions that would have transported additional larval sand lance from as far north as Nova Scotia. The same modeling indicated that larval sand lance originating on Stellwagen Bank transport south to the Great South Channel and Nantucket Shoals (but not Georges Bank). In some years, currents moved them as far as New Jersey.

This is just another example of the interconnected world that creates a productive marine environment. Since few sand lance in the study lived past three years, the dependence on shifting currents to populate the bank could be one thing responsible for boom and bust years typical of sand lance abundance. The team is currently examining genetics of sand lance taken from throughout the Gulf of Maine, the mid-Atlantic, and eastern Canada, to gain additional insight into population structure.

Do boom-bust years influence the distribution and abundance of predators? The team investigated the association of sand lance with humpback whales and great shearwater seabirds by placing satellite tags on both species to track their movements.

Throughout the Gulf of Maine, tracking revealed that both species spend the vast majority of their time over sand lance habitat, and DNA from fecal shearwater samples showed sand lance to be the bird’s main prey. Surveys in Stellwagen also demonstrated a high co-occurrence of sand lance, humpback whales and great shearwaters.

Sand lance feed primarily from February to July, mostly on Calanus finmarchicus copepods. They stop feeding from August through October, with low levels of feeding from the end of November to January. Body growth and fat content show similar trends, with length and fat stores increasing from February to July. After July, the fish retreat to bury in the sandy bottom, conserving energy for spawning.

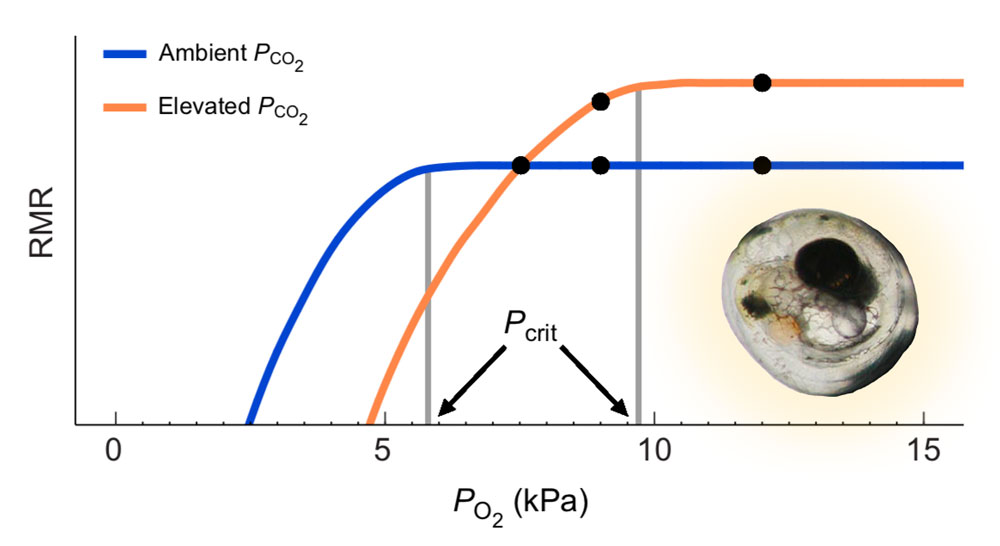

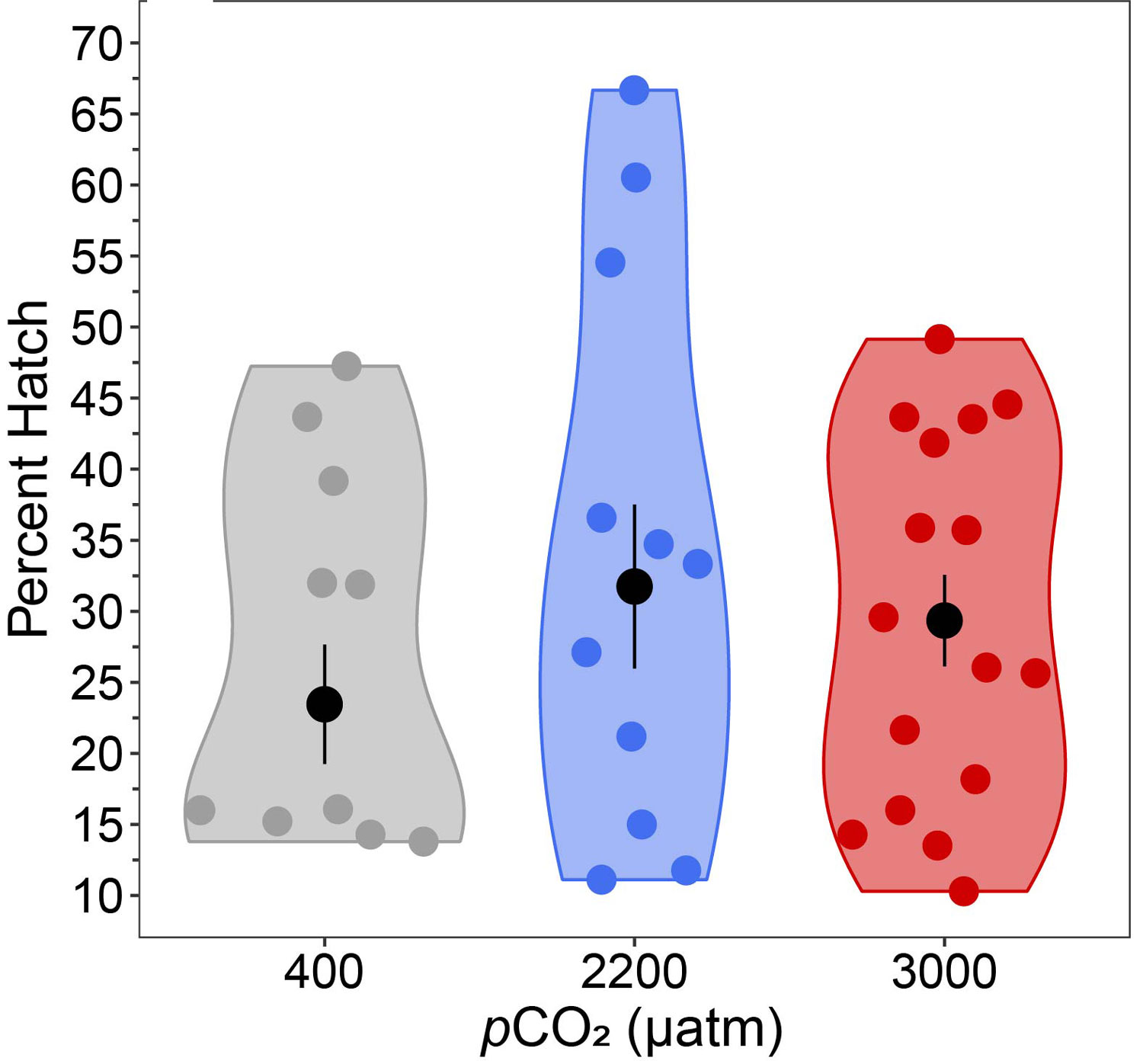

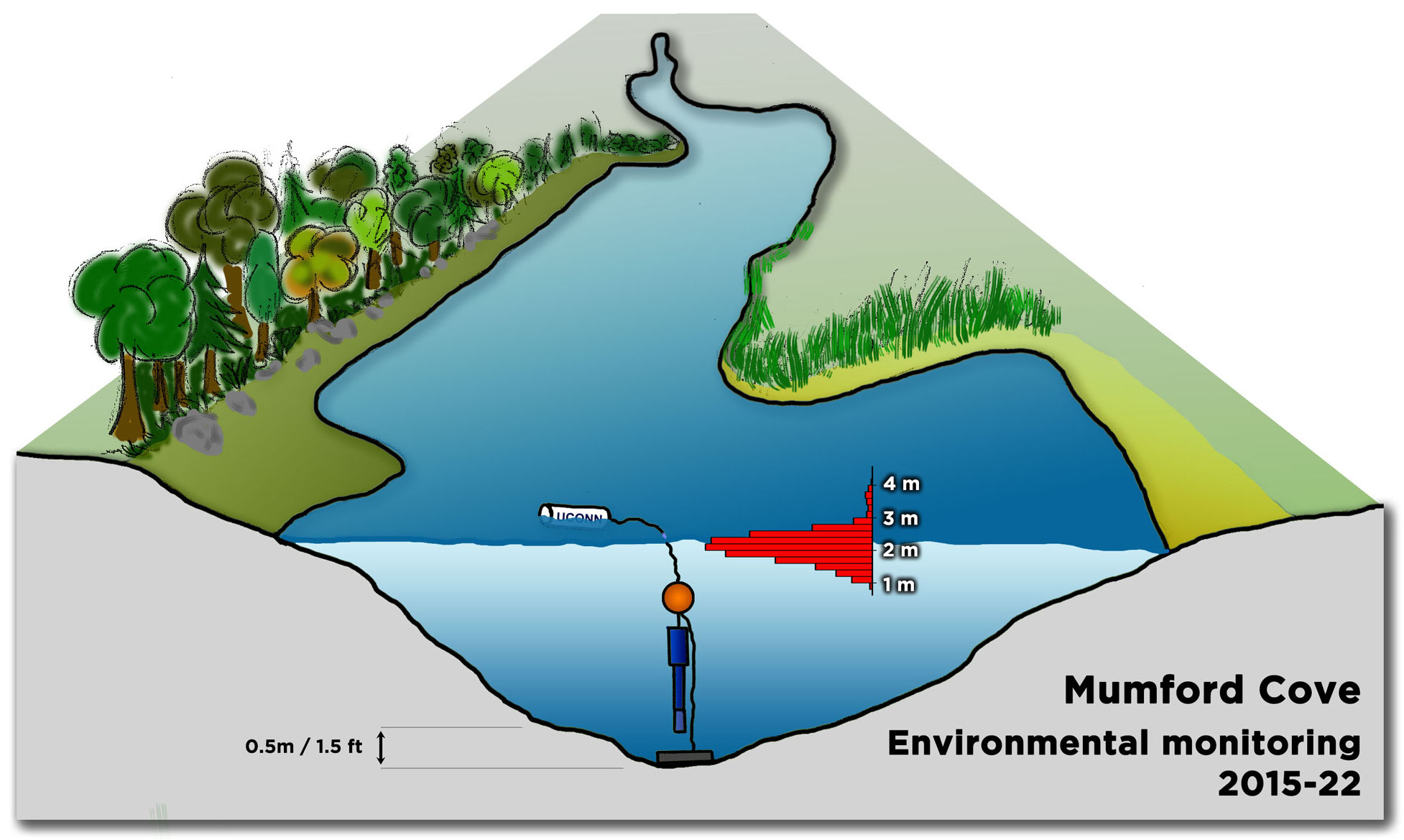

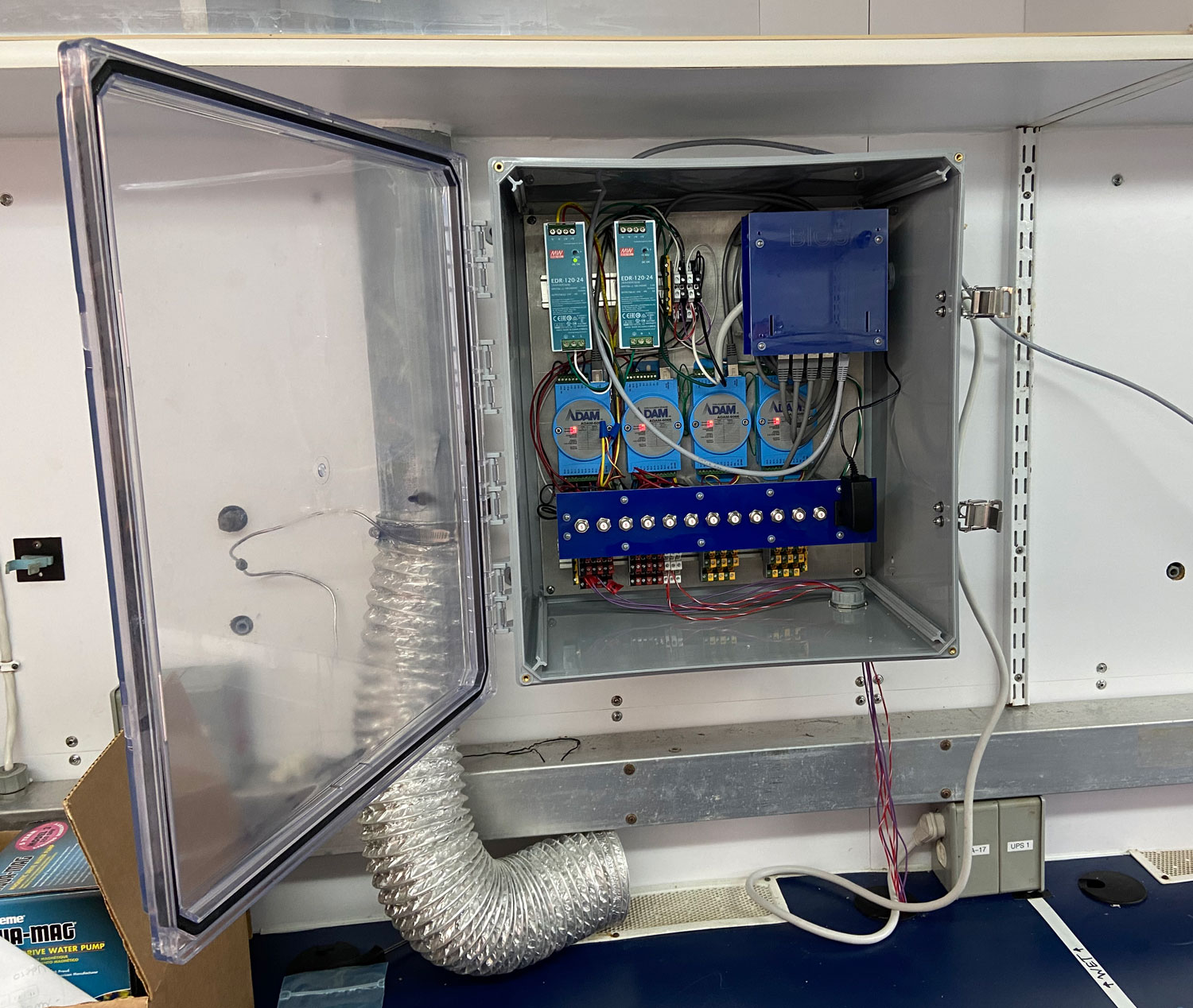

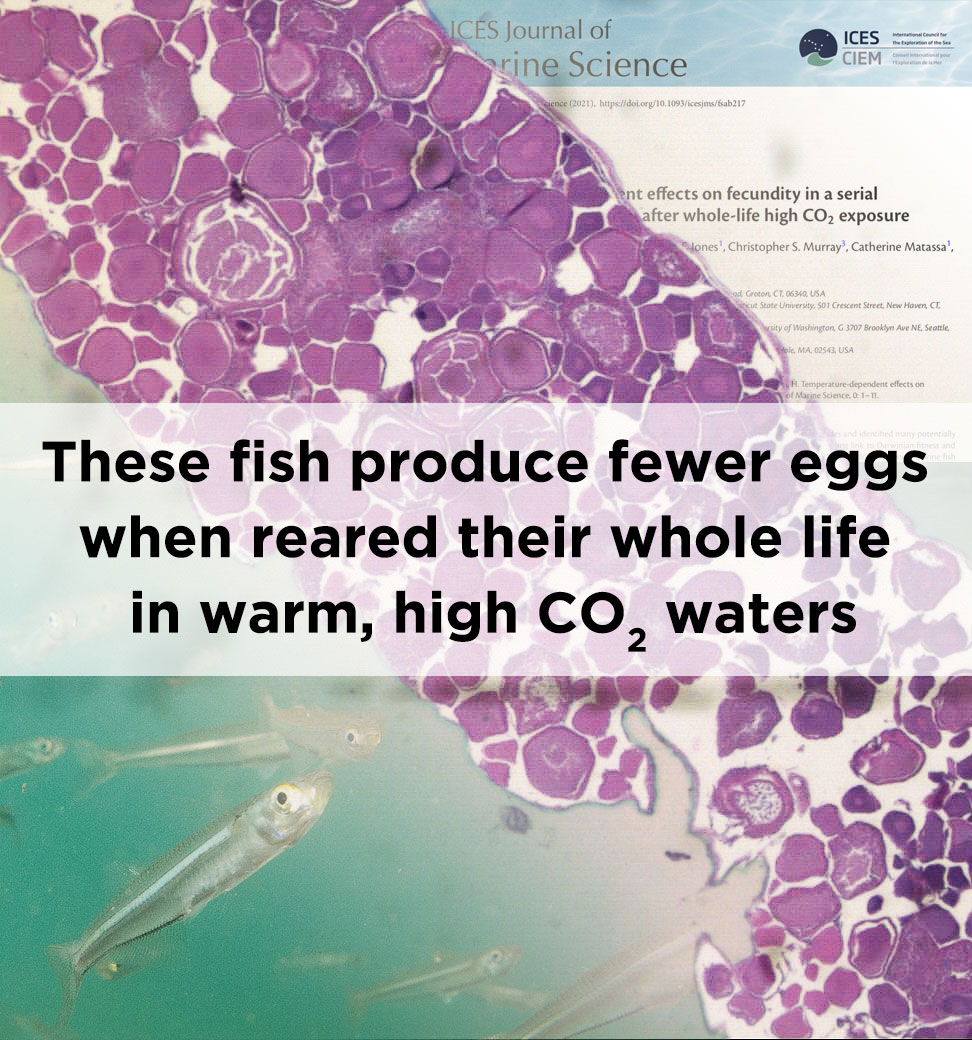

The team then turned its attention to the future of the valuable fish, something of extreme importance to fishermen. Ripe fish captured in November were strip-spawned on board the boats and transported to Connecticut, where eggs and larvae were raised in special tanks that allowed temperature and acidity to be manipulated to mimic future ocean conditions under climate change. Increased temperature and acidity had a dramatic negative impact on larval survival. According to Dr. Hannes Baumann, whose lab led the work, sand lance may be unusually sensitive to ocean acidification.

The future of sand lance was also a focus of team members Joel Llopiz and Justin Suca from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. They came to some worrisome conclusions.

The abundance of tiny C. finmarchicus copepods directly influences sand lance health: Abundant C. finmarchicus led to good parental condition and high reproductive success, while low numbers resulted in poor parental condition and poor reproductive success. Scientists have suggested climate change scenarios in the Gulf of Maine will lead to reduced abundance of this critical copepod resource. Adding to the problem was their finding that warm slope water coming through the Northeast Channel north of Georges Bank led to the death of overwintering reproductive adults.

With the Gulf of Maine warming faster than 99 percent of the world’s oceans, there is concern about the future of sand lance and its potential impact to the productivity of the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank and other areas. While states with fisheries and other marine resources supported by sand lance cannot solve climate change issues, they can work to make sand lance more resilient to climate change. One way is to eliminate as many non-climate stressors as possible.

For example, in 2020 Massachusetts promulgated a rule limiting daily sand lance landings to 200 pounds. Rhode Island followed suit in 2021. These rules were designed to discourage the development of a commercial fishery for the species, such as the huge industrial fishery in Europe’s North Sea.

Since a commercial sand lance fishery does not currently exist here, adopting this rule by other states would be an easy, proactive way to make our waters, and the people who depend on them, more resistant to climate change disruption.

(Dr. David N. Wiley is the Research Ecologist for Stellwagen Bank National Marine Santuary. Funding for the project was provided by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, The Volgenau Foundation, Northeast and Woods Hole Sea Grant, International Fund for Animal Welfare, Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary and the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. Dan Blackwood, Dr. Gavin Fay, Peter Hong, Dr. Les Kaufmann, Kevin Powers, Dr. Jooke Robbins, Dr. Tammy Silva, Mike Thompson, and Dr. Page Valentine contributed to the study)

Reposted from

Reposted from