reposted from UConn Today 30 April 2025

Fish that swam next to the dinosaurs are once again appearing in CT waters

By Elaina Hancock

For 160 million years, long-lived and highly migratory Atlantic sturgeons have made their way from the ocean to freshwater spawning grounds inland. The Connecticut River was one of the waterways sturgeon sought out – that is, until they were fished nearly to extinction in the early 20th century.

In 2014, however, researchers from the CT Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) caught a few juvenile sturgeons in the Connecticut River, implying that sturgeons were spawning there again. More little sturgeon appeared in 2020 and again in 2022, leading some to wonder if this iconic fish that swam next to the dinosaurs was indeed making a comeback in our regional waters.

A new study from UConn professors Hannes Baumann from the Department of Marine Sciences and Eric Schultz from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, in collaboration with researchers from CT DEEP including Kelli Mosca ’22 MS, Jacque Roberts, Thomas Savoy and Evan Ingram from Stony Brook University, shows that we have much to learn about sturgeons and that it may not be too late to give them a chance for recovery. Their findings are published in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s open access journal, Fishery Bulletin.

Baumann says the project started at a conference in 2019, when he connected with researchers at CT DEEP who pitched a potential collaboration with Mosca, who was a CT DEEP seasonal resource assistant at the time and was hoping to pursue a graduate degree and focus her research on sturgeon. Despite these sightings, Baumann says he was skeptical that the fish were having a comeback, but he was interested in the project.

“These fish spawn in freshwater and then they develop until they are about 50 centimeters in size, then they travel to the ocean so if you find a little sturgeon in the Connecticut River, it must have been born there,” says Baumann. “We know there are sturgeon entering the Connecticut River; then the question is, how far do they go?”

For the project, Baumann secured funding from Connecticut Sea Grant, Mosca joined Baumann’s lab, and they started analyzing data to study sturgeon movement in the Connecticut River.

In 1998, sturgeons became a protected species but only after their situation had become dire. They are now heavily regulated, and even getting permits for research is not an easy task, says Baumann.

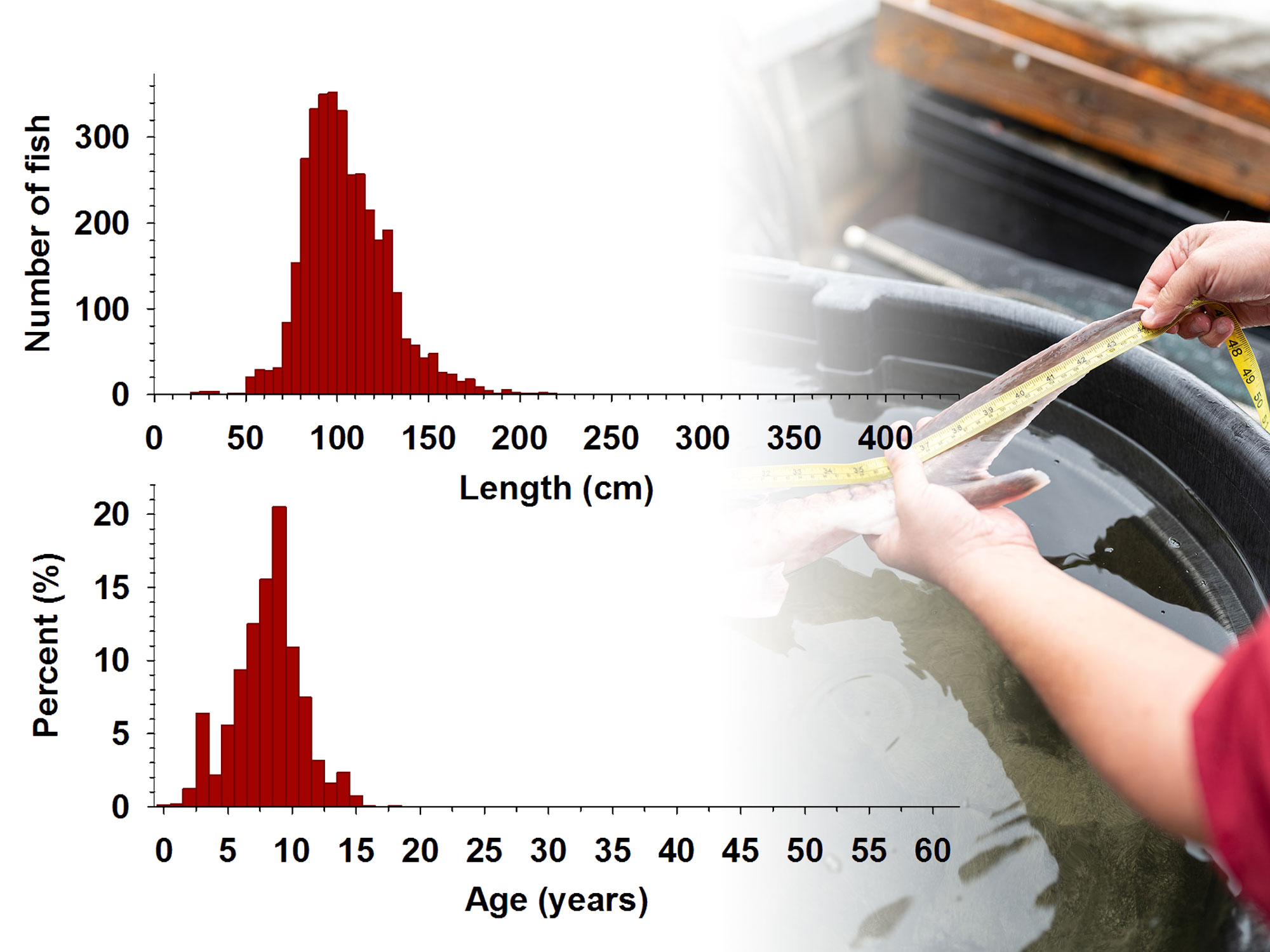

The researchers took samples of their pectoral fins that indicate the fish’s approximate age. Mosca looked at samples taken from the fish to determine the age,

“Ageing fish is often compared to ageing trees, in the sense that just as trees gain a ring in their trunk for each year they’re alive, a fish adds what we call an annulus (ring) to various hard parts in their body each year they are alive. In sturgeon’s case, they are not fully calcified, meaning there are not many hard bones to choose from to age. However, a small piece of their pectoral fin is hard enough to create those rings and can thankfully regrow so there is no deleterious effect on the fish. I am thankful to have access to such a large archive of these samples, which are rare given the endangered status of this species,” says Mosca.

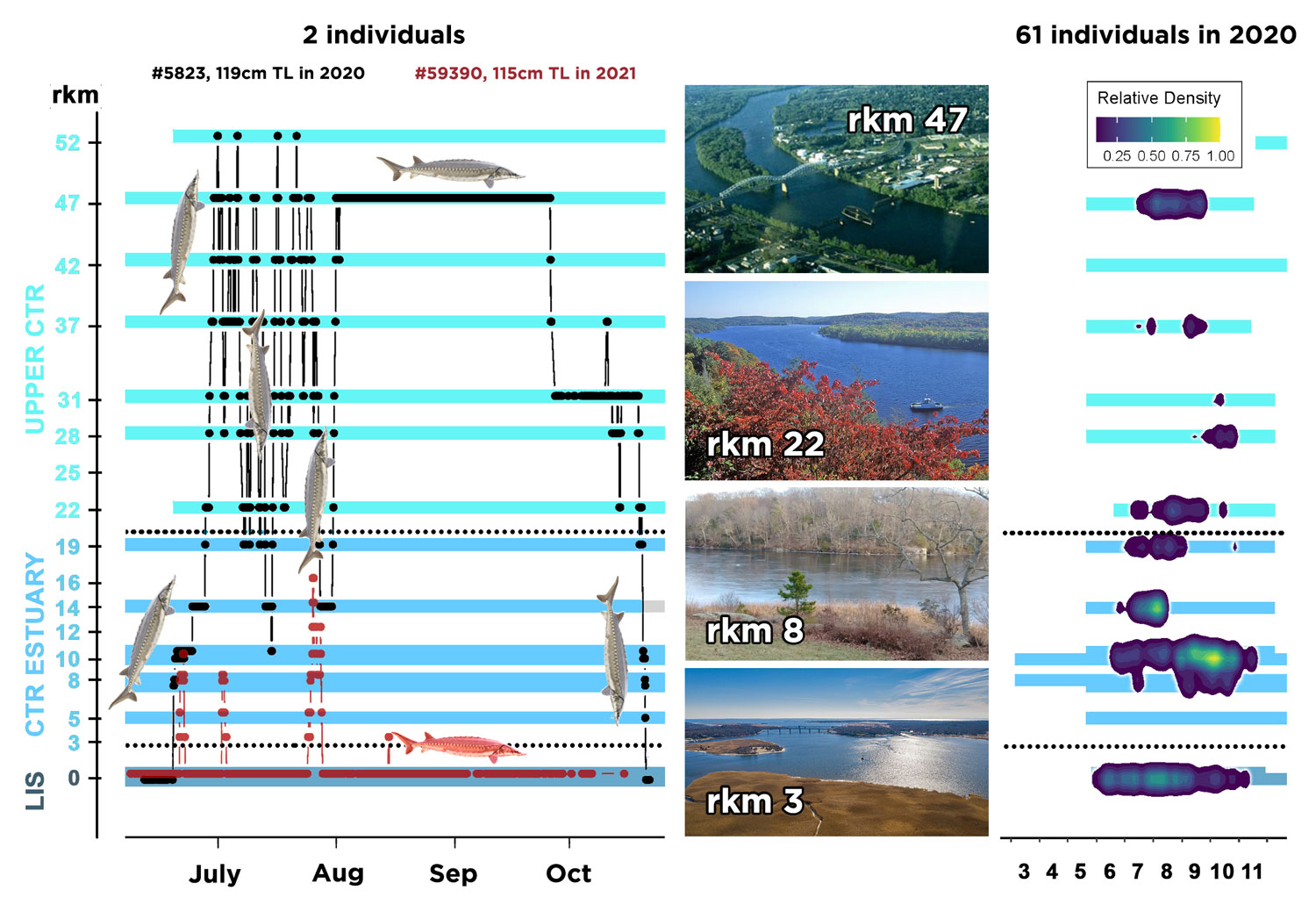

People have also tagged these fish with acoustic transmitters, a specialized tag that send out a signal which is then picked up by listening equipment called receivers. CT DEEP deploys receivers anchored along the Connecticut River and within Long Island Sound that record the tag data as tagged sturgeon swim by.

The researchers used data on tracked sturgeons over the course of the three-year study, and over that period, sturgeons were detected as far upriver as Wilcox Island (Middletown, at river kilometer 52).

“In theory, it’s all very easy, you just have to download the data and look where the sturgeon are,” says Baumann. “In practice, there are lots of statistics and analytical steps to properly assess these data. There were something like 1.5 million detections, over the three years in total, so 1.5 million rows of data, where every ping was a sturgeon somewhere. This corresponded to 85 individuals tracked over three years.”

Tracking animals in this way is called acoustic telemetry, and Baumann says the technology has profoundly changed our understanding of animal movements in the wild. There were some surprises in this one, he notes.

“Instead of just episodic accounts of single individuals, this study stands out for the large number of tracked fish,” says Baumann. “It showed that sturgeons generally arrive in the estuary in spring and leave in fall and that most stay in the brackish estuary. But intriguingly, a lot of the fish are indeed making these long upstream excursions into the freshwater. Why would they do this?”

Baumann says that the initial, most intuitive explanation of the fish displaying spawning migrations appeared unlikely after closer inspection. This is because most of the fish were not of adult size and age and, therefore, too young to spawn.

“We always thought Atlantic sturgeon are only in the estuary when they are young, and it is only when they want to spawn that they go into the freshwater. But that appears to be false. Our study shows that almost every size of sturgeon travelled into the freshwater portion of the Connecticut River. We had two individuals in our data set who were 18 years old. Most of the fish that we caught were younger than 12 years, and the average was about eight years, so they’re youngsters,” says Baumann.

The data therefore revealed that Atlantic sturgeons are using the entire Connecticut River, not just the estuary. Baumann says their working theory is that the fish are exploring other areas to find food, since the estuary can become crowded in the summer.

“In the paper, we advanced a theory that some of these Atlantic sturgeons move further up the river due to competition because it’s getting too crowded. The gist is we now know that we need to protect sturgeons at least during these important summer months, when they are in the entire Connecticut River.”

These findings are promising and important for ensuring measures are in place to help give the sturgeons the best chance possible at making a recovery. Though Baumann cannot say with certainty that the population is growing, a hopeful indication is that sightings of juveniles likely born in the River are happening more frequently.

“The sightings are still very sporadic and sort of ephemeral, but perhaps it’s a start.”

Protecting a highly mobile species like sturgeons can be tricky because they recognize no borders. Therefore, it takes national, federal, and international cooperation, but other measures are also important to ensure people are aware of their presence to help reduce accidental boat strikes or bycatch in commercial fisheries.

“From a logical perspective, they have been fished to quasi extinction in the beginning of the 20th century. Indeed, it would be a small miracle if these fish came back,” says Baumann. “At the end of the day, they made it 160 million years, and we need to just give them a chance to make it another 100. It doesn’t take much. It does take time, but if we allow it, I’m convinced that nature will find a way.”

- Mosca, K.C., Savoy, T., R. Benway, J., Ingram, E.C., Schultz, E.T., and Baumann, H. (2025) Age structure and seasonal movement patterns of Atlantic sturgeon aggregating in eastern Long Island Sound and the Connecticut River Fishery Bulletin 123:127-142