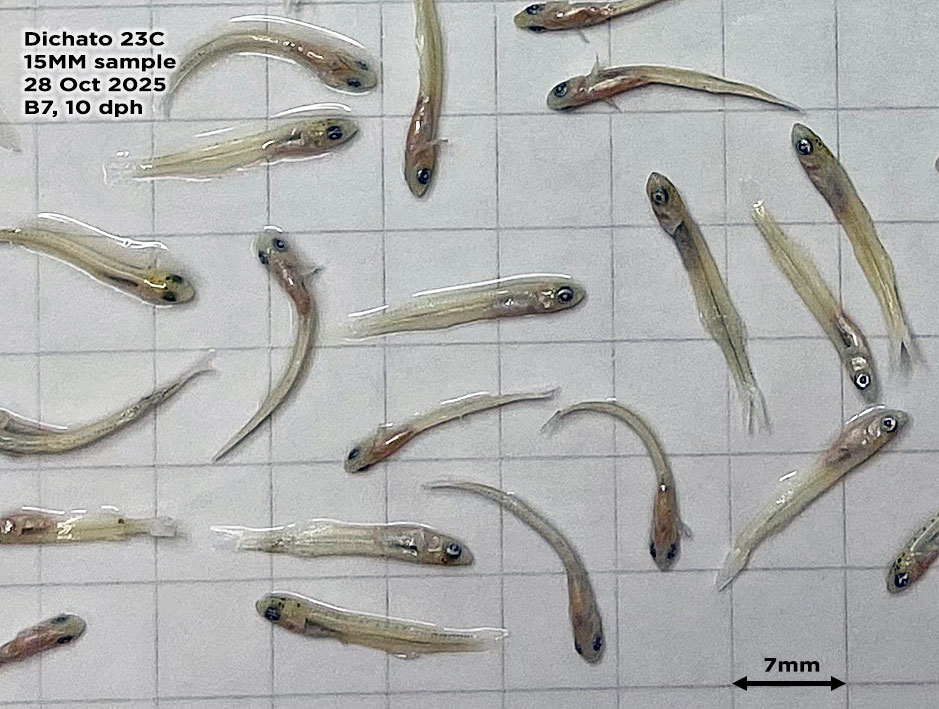

22 December 2025. Shortly before Christmas, a cloudless blue summer sky stretches endlessly over Dichato. The summer vacationers now arrive in troves in this small Chilean village. Hannes just returned again for a few short days to help end the second common garden experiment at the Marine Station, preserve all sampled specimens, and ready them for their journey to Connecticut. The days are filled with bittersweet emotions, as one chapter ends while marking the beginning of the data analysis phase of the whole project.

For more than 5 weeks, research technician Tamara Cuevas diligently attended to the experiment while Hannes finished teaching his class at UConn. Tamara successfully executed the daily husbandry, feeding, testing, the frequent sampling events, while reacting nimbly to all the unforeseeable, yet inevitable things that came her way. Tamara, you're truly the hero of this second experiment, well done!

Meanwhile, Hannes used his third journey to the southern hemisphere to make a few stops along the way. In Lima (Peru), he met with Victor Aramayo, a biologist at the Peruvian Institute of Marine Research (IMARPE), to receive silverside samples from two locations in Peru. He then traveled to Valparaiso (Chile) to meet with Prof. Mauricio Landaeta (Universidad de Valparaiso), who contributed samples from the southernmost silverside species (Odontesthes smitti) from Punta Arenas in Chile's far south. He flew for a day trip to Antofagasta (Chile) to meet Prof. Marcelo Oliva (Universidad de Antofagasta) who contributed specimens from this particular locale. All together, we now have silverside samples from 7 populations spanning 45 degrees of latitude (9-54S) for genomic analyses!

As Hannes shakes hands and emotionally says good bye to his Chilean friends and colleagues, it is the excitement for the findings to come that shines as bright as the December sun over Dichato.

Saludos y feliz navidad!