On this dimly lit November afternoon, rain mercilessly drenched scientists and crew on board the R/V Auk as it slowly navigated the waters of Stellwagen Bank. A world like a wet sponge. Sky and ocean, indistinguishable.

Thanksgiving, the next day.

Despite the circumstances, the team’s mood was nothing short of elated. Our small beam trawl had just spilled hundreds of silvery fish on deck, wriggling like eels. They were Northern sand lance (Ammodytes dubius).

Running ripe adults.

Spawning.

Apparently, they like Thanksgiving, too.

—————

As the ship docked back in the Scituate, Mass., harbor that day, the rain thinned to hazy darkness.

“Let’s get a coffee and then on the road,” mumbled Chris, who led the team, “the real work of the experiments has just begun.”

Sand lance have a few interesting and rare characteristics. They alternate between schooling and foraging in the upper water column and extended periods of being almost completely buried in sand. For that, they rely on sand of a particular grain size and with very little organic content. It’s the kind of sand that defines large areas of the Stellwagen Bank.

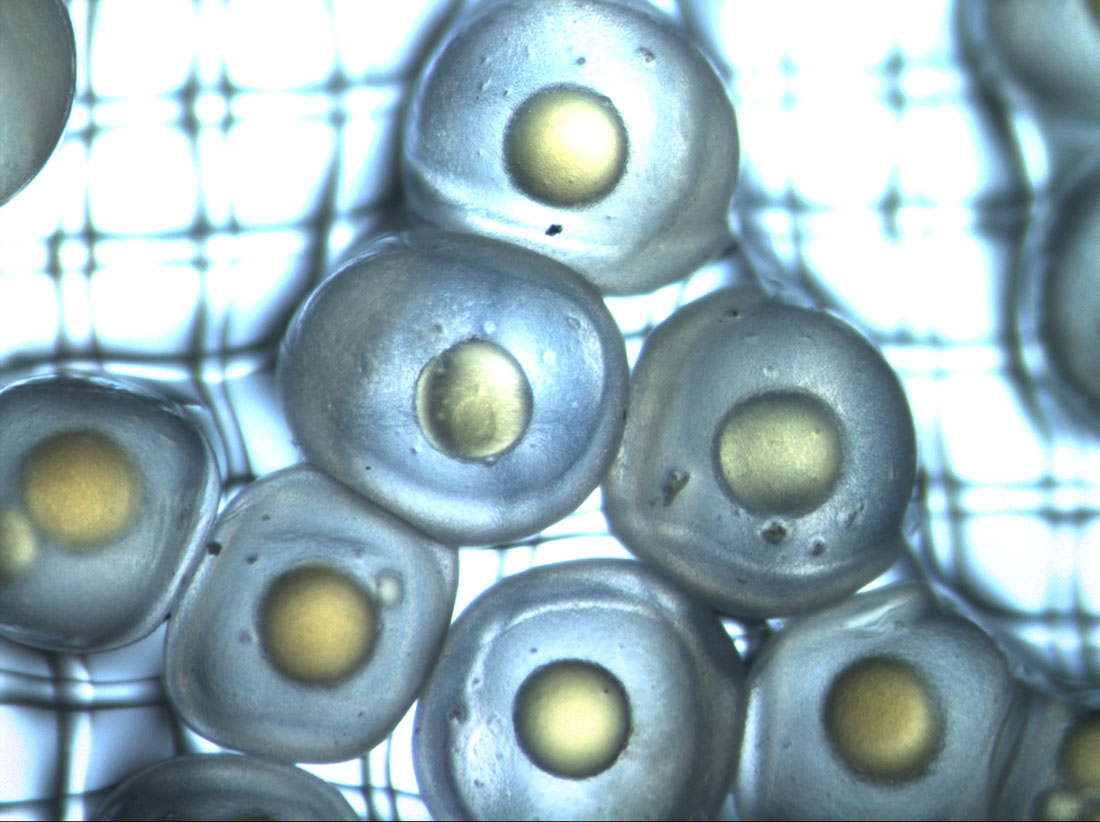

Surprisingly little is known about the ecology and ecosystem importance of this sand lance species, although research on its European relatives (A. tobianus, A. marinus) is more advanced. In particular, experiments on early life stages of Northern sand lance have been lacking, save for some pioneering work on rearing methods of the related A. americanus (Smigielski et al. 1984). One question that was of particular interest to our lab involved the potential sensitivity of this fish species to carbon dioxide (CO2). That’s due to two other interesting and rare characteristics of sand lance. They spawn in late fall and winter in cold (and still cooling) waters, which is why their eggs and larvae develop extremely slow compared to other, more typical spring and summer spawning species. In addition, the species is found not in nearshore, but offshore coastal waters, where smaller seasonal and daily CO2 fluctuations more closely resemble oceanic conditions. Could sand lance offspring be particularly sensitive to higher levels of oceanic carbon dioxide predicted during the next 100 to 300 years as climate change effects intensify?

Our experiments are still ongoing, and rearing protocols are being improved.

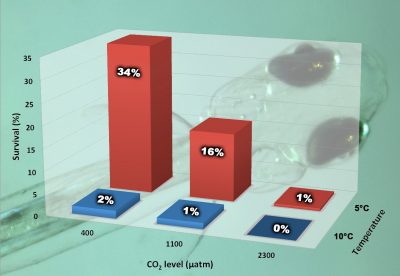

The preliminary findings, however, are stunning. Survival to hatch was dramatically reduced under elevated and high compared to baseline CO2 conditions. It was severely lowered at higher (10°C or 50°F) compared to lower temperatures (5°C or 41°F). Our second experiment this year appears to repeat this pattern. If these results continue, that would mean sand lance is one of the most CO2-sensitive species studied to date.

General interest in sand lance goes beyond its sensitivity to carbon dioxide. Given the species importance for the ecosystem and coastal economy, there are now increasing efforts to better understand sand lance feeding ecology, distribution and relationship to the rest of the food web. In this regard, funding of our project by the Northeast Sea Grant Consortium proved prescient and a seed for subsequent grants from MIT Sea Grant and the Bureau of Energy Management (BOEM) to continue the work. Surely, the groundswell of interest in sand lance is commensurate with its importance and will enable insights into better management strategies for sensitive ecosystems like those along the U.S. Atlantic coast.

Collaborators on this project are: D. Wiley of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary; P. Valentine of the U.S. Geological Survey; and S. Gallagher and J. Llopiz, both of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.