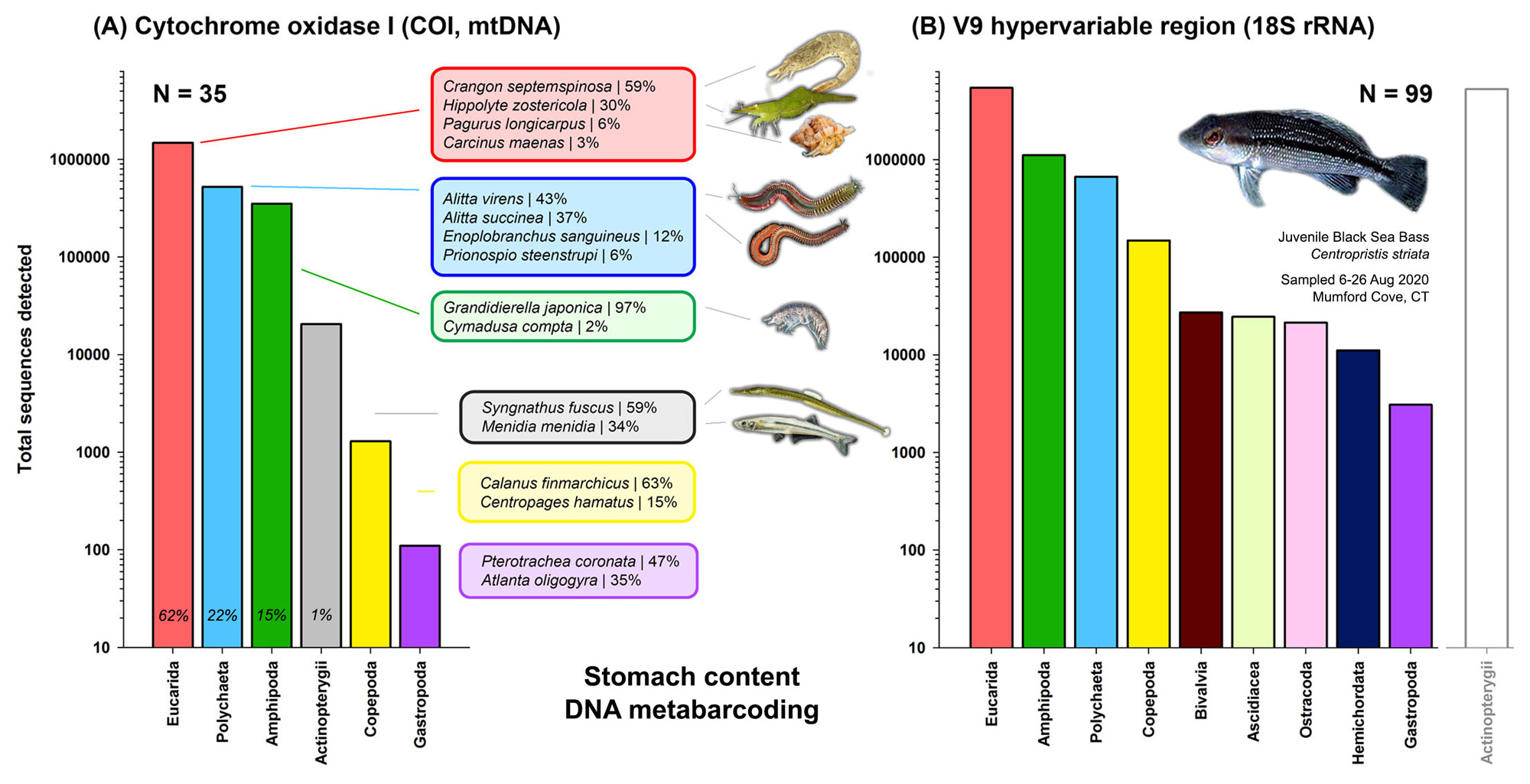

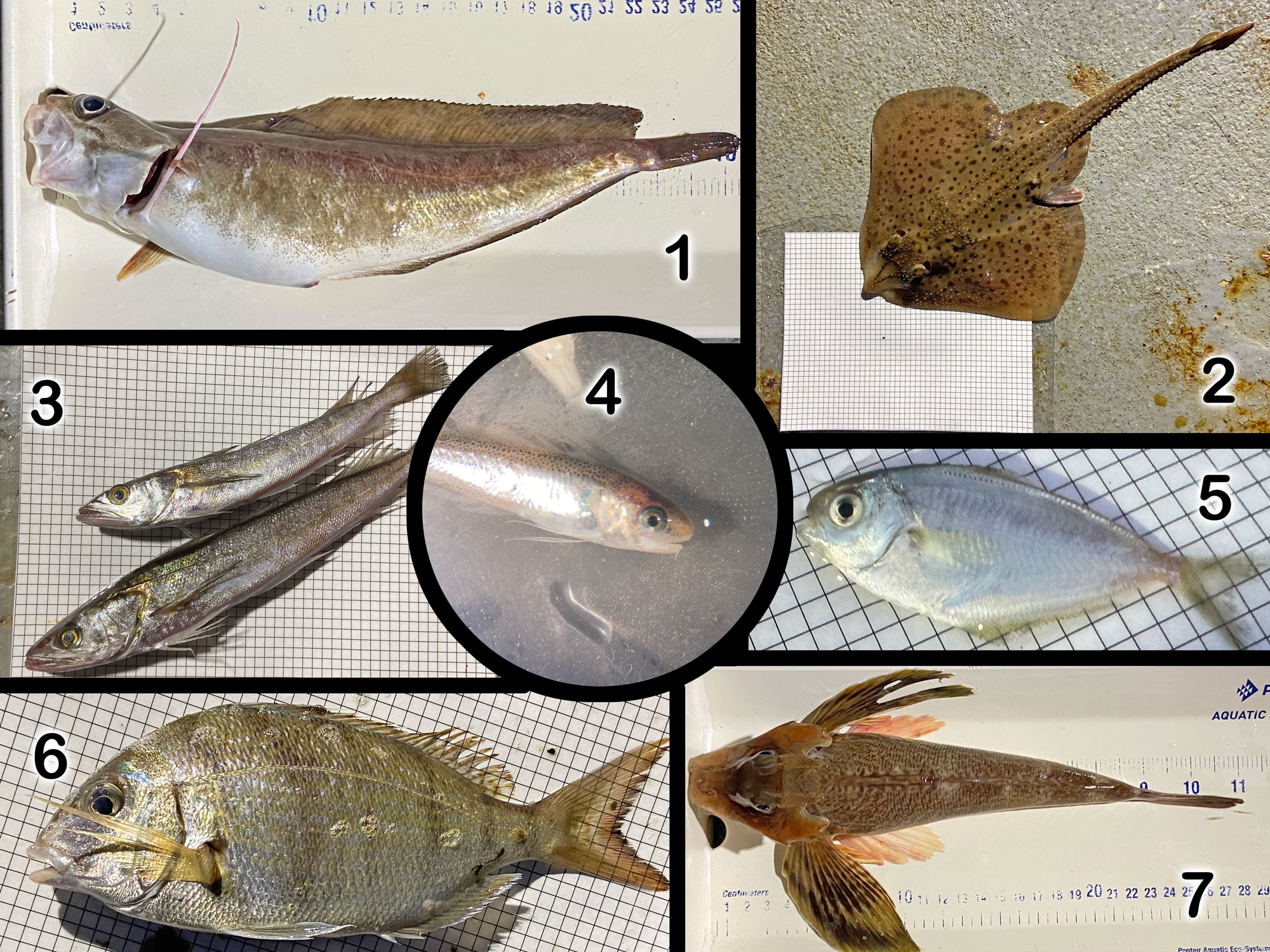

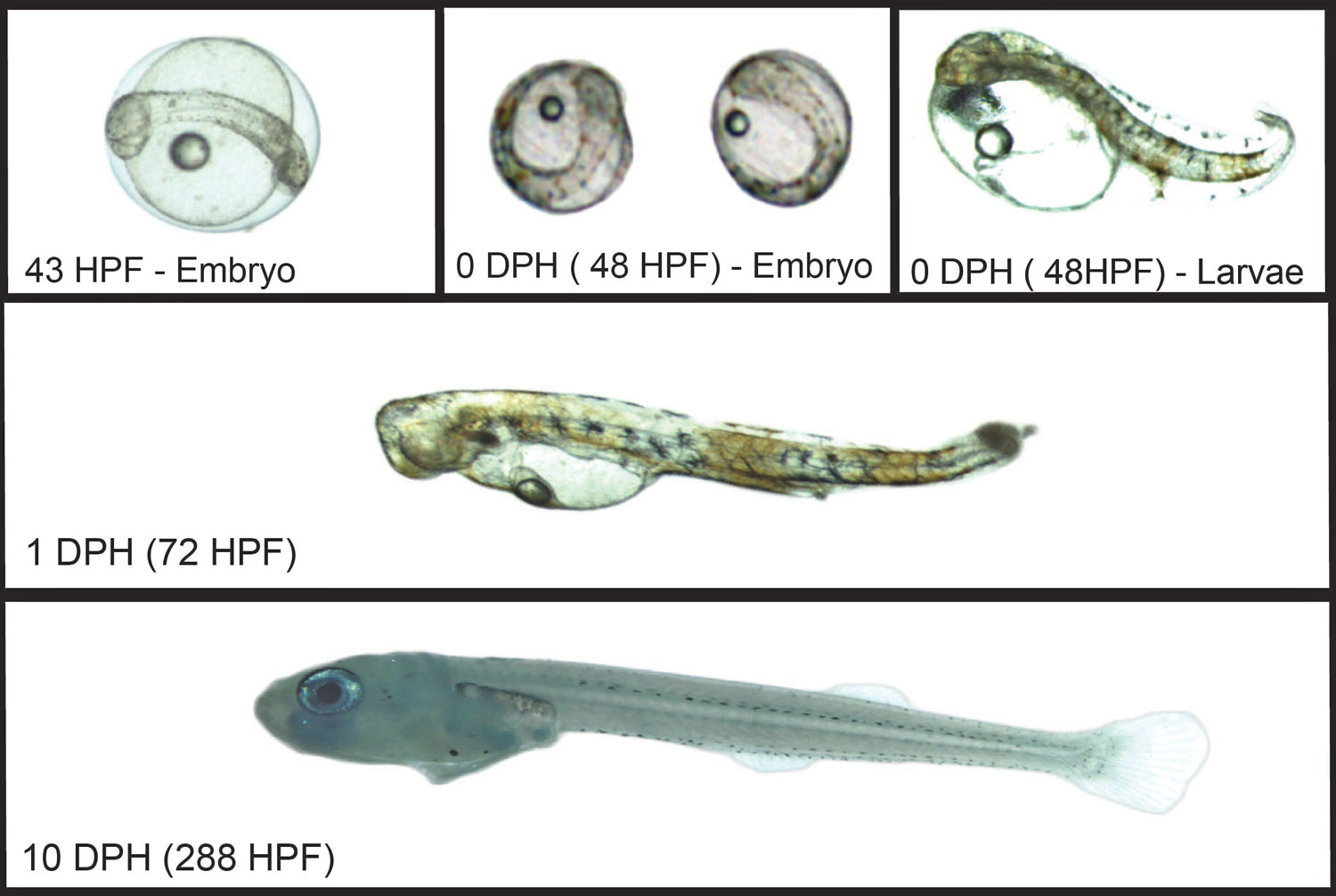

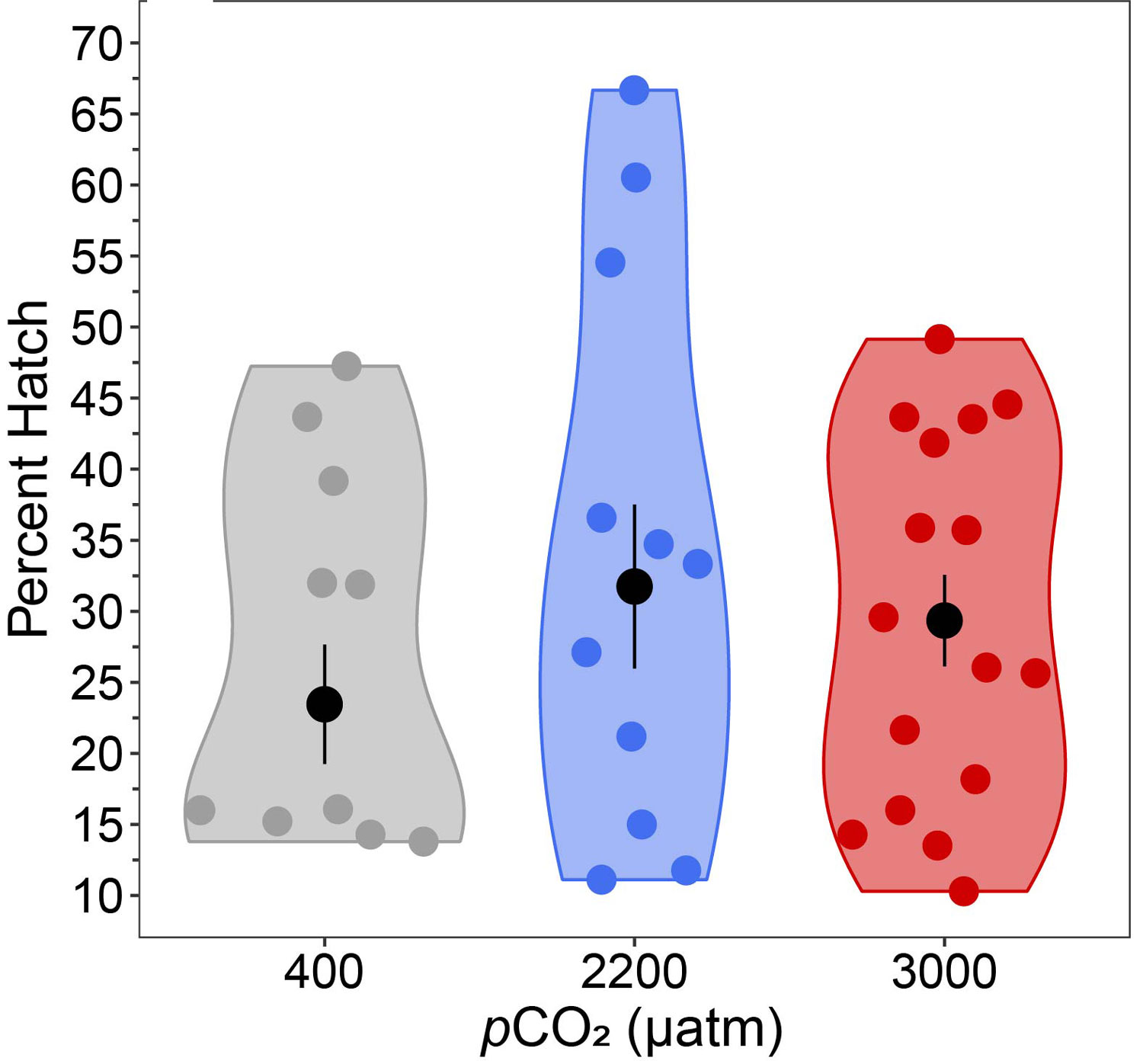

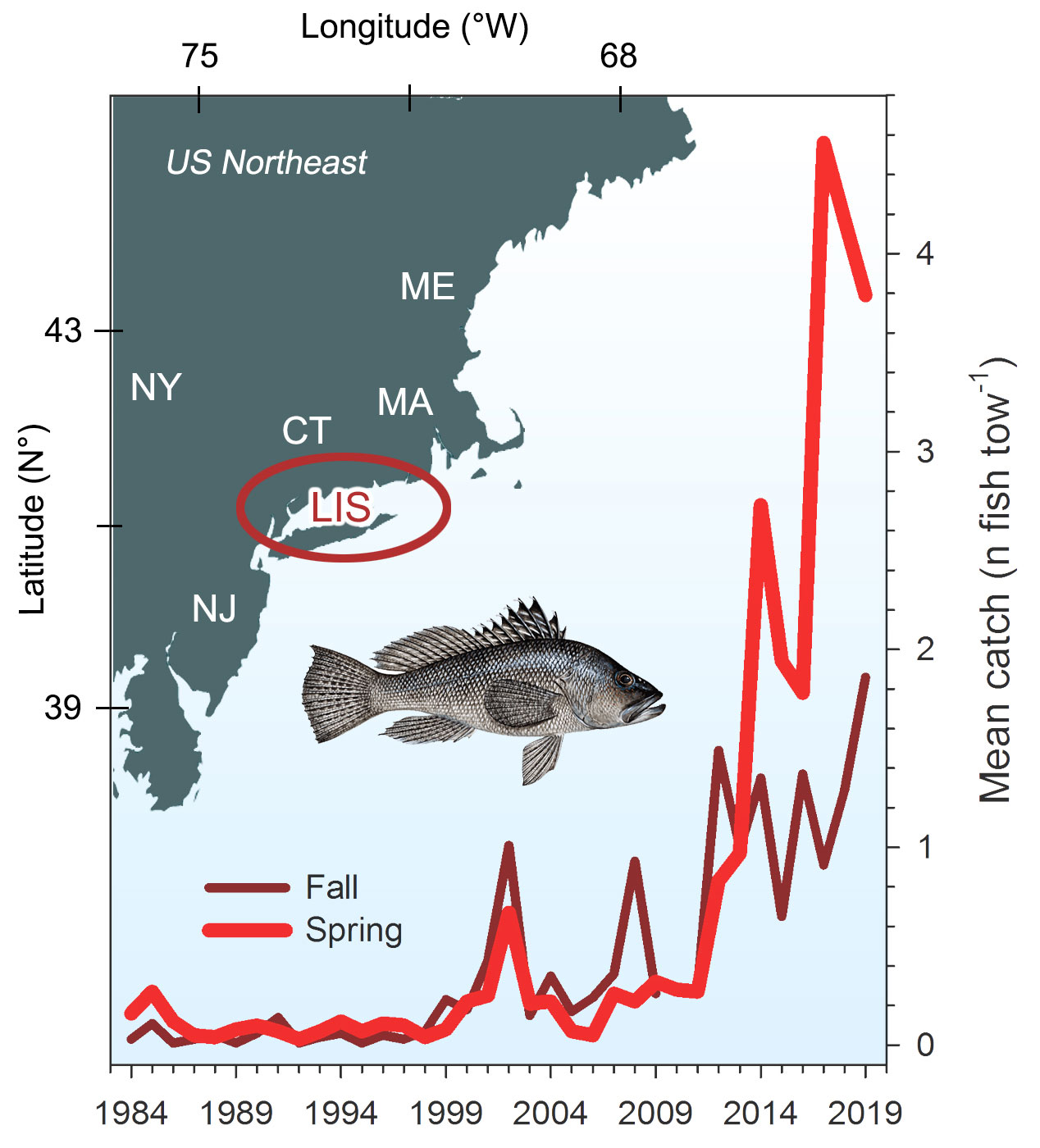

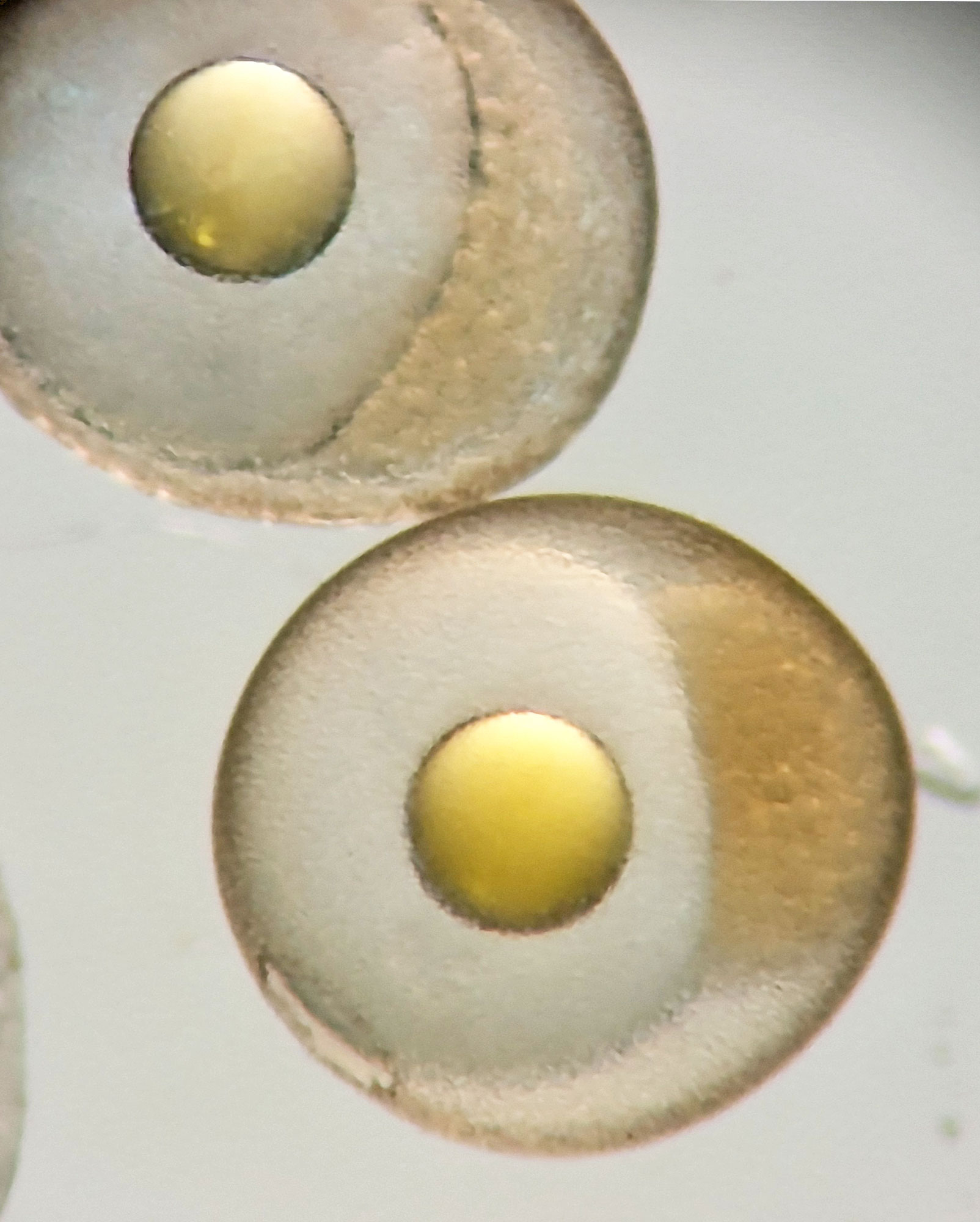

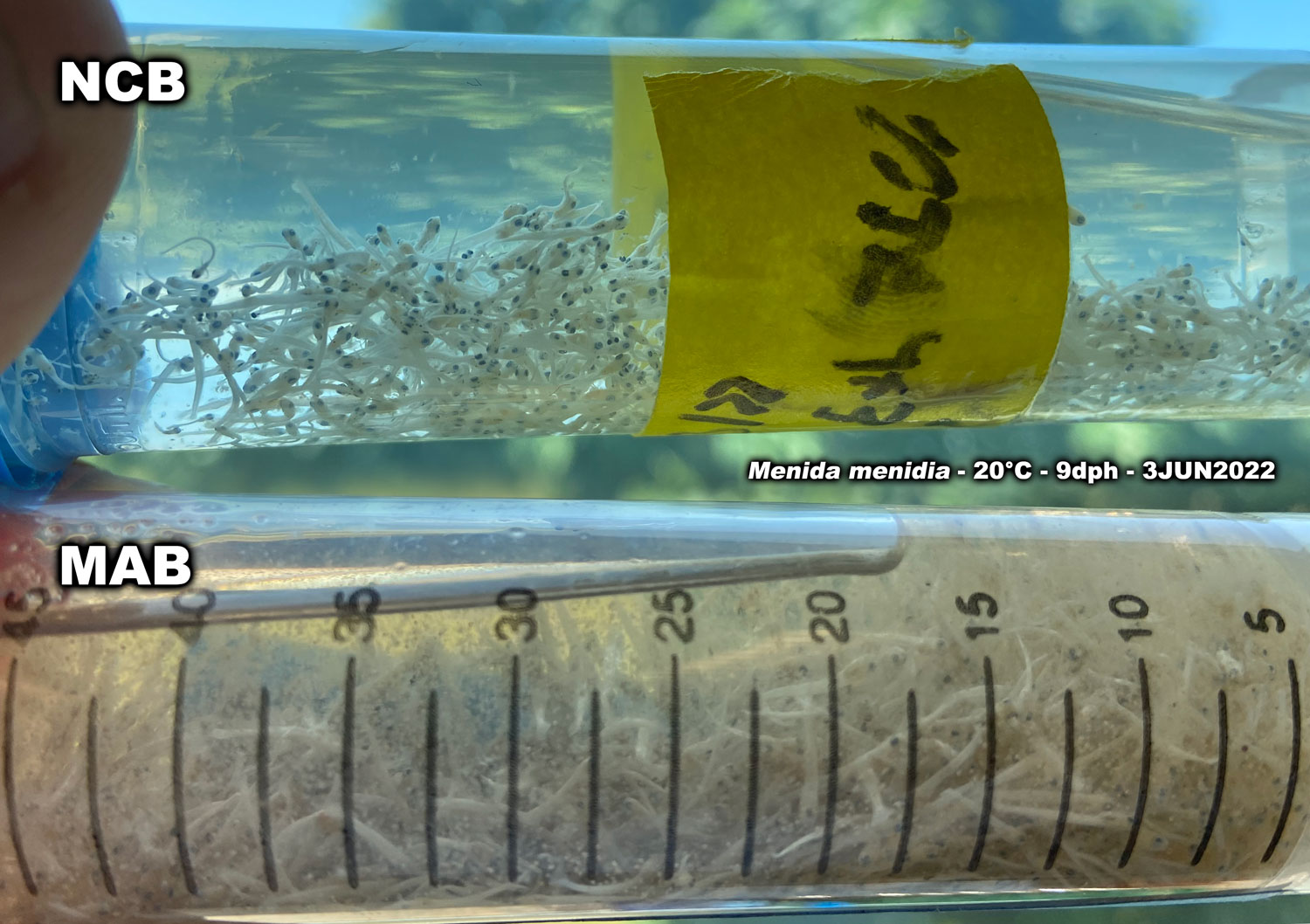

22 November 2024. We are happy to share that our paper on black sea bass stomach content metabarcoding has been published today in the traditional NOAA journal Fishery Bulletin. Our study used black sea bass juveniles caught in Mumford Cove to study their diet via a molecular approach known as metabarcoding. This method often detects rare or soft-bodied prey better than traditional morphological content analyses. We found that small, newly settled black sea bass eat mostly shrimp, but also many softbodied polychaetes. And weirdly, they seem to like one particular kind of (invasive) amphipod. Only larger juveniles seem to add fish to their diet.

Our study is a great first collaboration between our departments genomic experts (Ann Bucklin, Paola Batta-Lona) and the Evolutionary Fish Ecology Lab. The first product of our collaborative efforts has seen the light!

Fishery Bulletin is the 143 years old peer-reviewed journal managed and published by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) of the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It publishes Open Access at no costs to authors. Click the link below to download the paper.

- Batta-Lona, P.G., Wojcicki, M.L., Zavell, M.D., Bucklin, A., and Baumann, H. (2025)

Using DNA metabarcoding to reveal prey diversity in diets of juvenile black sea bass (Centropristis striata) in Long Island Sound in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean.

Fishery Bulletin 123:22-33